Table of contents

For me, logic is much more than a writing skill.

I see it as the "IT" factor that makes writing worth while.

For someone who has employed logic in their writing for years, much of its power is done unconsciously.

It took me almost two months to reverse engineer all of my logical thinking strategies and reveal them in a blog post. I experimented long and hard to create systems you can employ to remove logical fallacies from your writing.

Now they’re complete.

In this guide you’ll find:

- What happens when you deter from a logical arc

- 11 logical analysis fallacies (with examples and tools for detecting them)

- How to use logical fallacies intentionally

- 3 (personally verified) resources for improving your logical reasoning

- A note on how fallacies emerged and how you can deal with them

So, let’s dig in.

What happens if you deter from a logical arc

If you don’t follow a logical arc, here’s what happens:

- Your readers have a terrible reading experience

- Your ideas are perceived as less credible

- Your authority as a writer plummets

11 Faulty logic examples (that I see every day as a writer):

1. Anecdotal fallacy:

The anecdotal fallacy is a fault logic example where an argument based on personal experience or isolated example rather than evidence.

The prevalence of UFOs, some herbs as medication, and belief in ghosts are common anecdotal policies.

Here are some common phrases people use to justify them:

- “But I saw a UFO with my own eyes”

- “I know someone who once had a magic spell cast on them”

- “I know an expert who said rallies for herbal medication”

- “I’ve seen a photo that had a UFO”

- “The government is trying to keep us in the dark”

Now all of these might seem valid arguments on the face of it but each of them hinge on one person’s experience. Even worse, some simply re-tell another person’s experience, which is even less credible.

2. Straw-man fallacy

The straw-man fallacy occurs when an argument is misrepresented to make it easier to attack. Essentially, setting up a “straw man” (or false victim) to take the blame.

Here’s an example of it in action:

Even though Lila never said she believed her commitments are more important than her friends’, this is how it was presented by Tina. In the way Tina has structured the argument it is easy to blame Lila for being selfish and taking her friends for granted.

3. Ad Hominem fallacy

Attacking the person making the argument instead of addressing the logical reasoning of the argument.

Here’s an example of this logical fallacy from Harry Potter highlighting it:

Rather than debate about Hermione's actions or arguments, Bellatrix dismisses Hermione based on her pure-blood status. This is ad hominem at work.

4. No true scotsman fallacy

This occurs when an argument attempts to redefine a term or group in order to exclude counterexamples.

Another Harry Potter faulty logic example alert!

Original premise: The Death Eaters are pure-blood supremacists

Intended takeaway: Death Eaters are bigoted and exclusive

Critical fallacy: The term "Death Eater" is redefined to exclude counterexamples of those with mixed heritage.

Here’s an example of those of you who are unfamiliar with Harry Potter:

See how the manager redefined the term ‘intern’ to exclude paid interns? Classic ‘no true Scotsman’ fallacy.

5. Non sequitur fallacy

An argument's conclusion does not logically follow from its premises.

Here’s an example:

This is an example of non sequitur fallacy because the statement presents the word "theory" as if it means a guess. In science, a theory is an explanation of a phenomenon that has been repeatedly tested and supported by evidence.

Here’s another example:

This is non sequitur fallacy at work because the statement presents one person's experience as evidence that vaccines are not safe, and it doesn't follow that just because someone got sick after getting vaccinated, all vaccines are dangerous.

Note that this is also an example of the anecdotal fallacy. (Fallacies sometimes overlap, it’s okay.)

6. Appeal to emotion fallacy

This occurs when an argument uses emotions to manipulate rather than providing logical evidence.

We’ve all done this. We’ve all had this done to us. When a friend or a loved one tries to convince us to go to an event we are in no mood for? By saying something along the lines of “Oh come on, don’t you even love me enough to do this for me?”

Even though this is a very compelling statement, it doesn’t follow from logic.

A logical argument would’ve been:

7. Appeal to ignorance

This occurs when you’re asked to believe something to be true just because there’s no argument/theory disproving it.

There is no conclusive evidence that genetically modified foods are unsafe, but that doesn't necessarily mean they are safe. This statement illustrates the appeal to ignorance fallacy.

Here’s what else it could mean:

- More research is needed to understand the risks and benefits of consuming genetically modified foods.

- Limited scope: The studies that have been conducted have a limited scope, they may not have examined long-term effects or specific groups of people.

- Research bias: studies may be funded by companies that produce genetically modified foods may have an incentive to show these as safe.

8. Circular argument

This happens when an argument goes round and round without concluding anything new.

Here’s an example:

This statement uses the existence of God as proof of the validity of the Bible and then uses the Bible as proof of God's existence. It’s a circular argument because it assumes that God exists without providing any evidence to support that claim, and uses the Bible to support the existence of God, when the Bible is assuming the existence of God in the first place.

9. Red herring fallacy

This happens when someone introduces a topic irrelevant to the issue, to divert attention from the lack of evidence or weakness in their own argument.

Here’s an example:

Here the speaker tries to divert from the topic of gun control by introducing another pressing problem. He bridges the transition by arguing that mental health resources are “the bigger problem.” However, whether mental health resources are present is irrelevant to the issue of gun control.

This is a classic red herring fallacy.

This is a straightforward example but a lot of content I’ve read online uses the red herring fallacy in round about ways, making it trickier to spot.

To spot these (and avoid them myself) I try to identify the consistency in arguments by writing down every sentence in a simpler fashion.

Let’s look at this example:

In this example, the speaker is trying to argue against the bill to increase funding for education by introducing a series of red herrings.

- The first red herring: the claim that the bill will lead to higher taxes for the middle class and strain their budget, which is not directly relevant to the bill.

- The second red herring: the claim that throwing money at the problem doesn't always solve it and the example of foreign aid which is not directly relevant to the bill.

- The third red herring: the claim that the bill is a thinly veiled attempt by politicians to pander to special interest groups and secure their own re-election which again is not directly relevant to the bill.

Rather than providing logical or factual evidence against the bill, these red herrings are intended to distract from the main argument.

Here’s how I use Wordtune to deconstruct arguments into simple parts so I can identify red herrings.

Simpler version of the idea: Increasing education funding is a bad idea because it will increase middle class taxes.

Simpler version of the idea: Additionally, budgets are already stretched, and throwing more money at problems may not always solve them.

(In Wordtune’s reframing of this sentence, we notice that the structure of the argument completely falls apart.)

When this happens in multiple Wordtune rewrite options, that’s when I consider the argument to have a logical fallacy.

Simpler version of the idea: We've spent a lot on foreign aid, but many countries we've helped are still suffering economically and politically.

Simpler version of the idea: Politicians are trying to pander to special interest groups and secure their own reelection by passing this bill instead of addressing the root causes of our education system's shortcomings.

Now when we put together all the simpler versions of the idea, we can identify the red herrings and logic fails easily.

These sentences are clearly disconnected and are not based on reasoning, but rather on distraction tactics.

10. Slippery slope argument

This happens when a certain set of starting circumstances is assumed to have a definite consequence. But these consequences don’t always follow from logical deduction.

Here the speaker is arguing against same-sex marriage by suggesting that it will inevitably lead to the legalization of other forms of marriage that are considered morally unacceptable, such as polygamy and bestiality.

Here’s how I use Wordtune to draw out slippery slopes:

Simpler version of the idea: The legalization of same-sex marriage would lead to polygamy and bestiality. (Wordtune’s reconstruction of this argument automatically calls out the ‘slippery slope’ in this case.)

Simpler version of the idea: In no time, our society will be in moral chaos as people marry anything and everything.

Simpler version of the idea: In order to preserve the traditional institution of marriage, it must remain between one man and one woman.

Here’s what this ideas look like when you put the simpler sentences together:

It’s evident that there is a gap in the logical reasoning of this sentence. The conclusion doesn’t naturally follow from the premise.

11. Tu quoque fallacy

In this argument, the person defending his or her own actions or beliefs claims the other person is also guilty of the same.

Here’s an example:

In this scenario, candidate B is committing the tu quoque fallacy by deflecting accusations of corruption by pointing out that candidate A has also accepted donations from special interest groups and has had staff members who were involved in misconduct.

While these are relevant issues, they do not excuse or justify candidate B's own alleged corruption and unethical behavior.

Also, the argument implies that because candidate A has also faced similar issues, candidate B's own actions are acceptable. This is fallacious reasoning because past mistakes or misdeeds by candidate A does not excuse or justify any wrongdoing by candidate B.

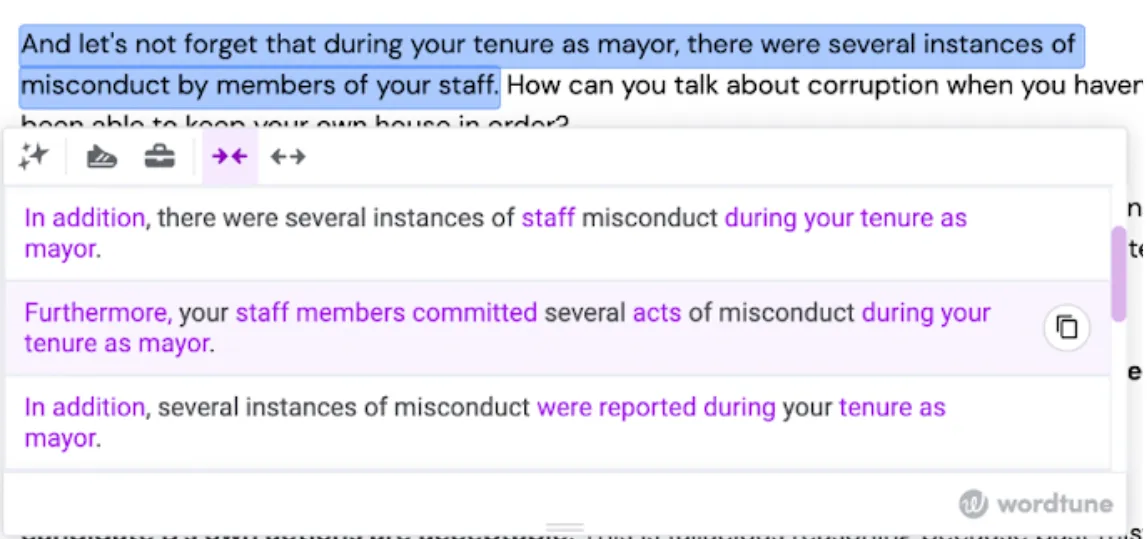

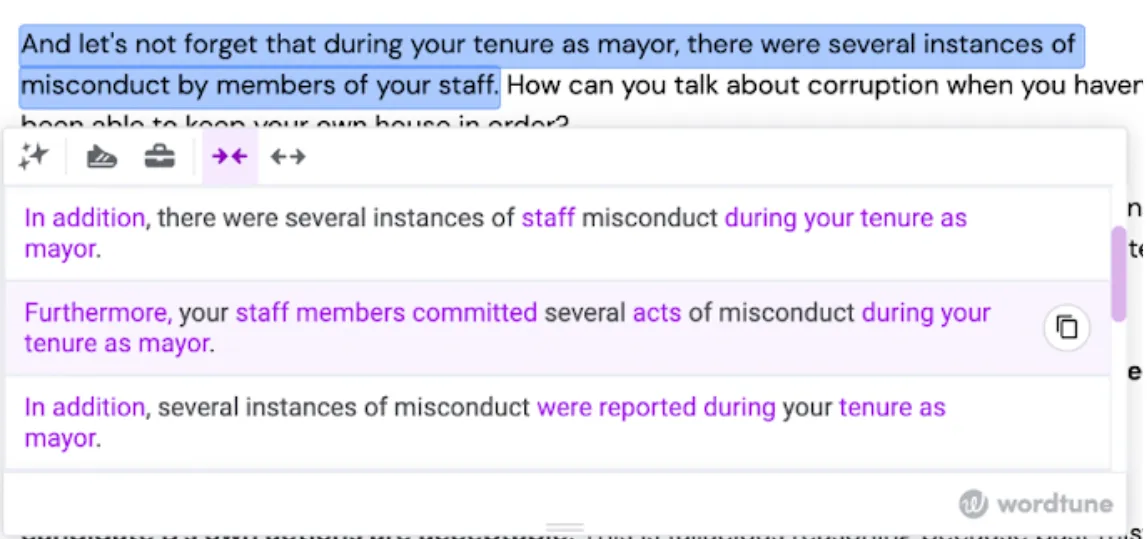

Here’s how I use Wordtune to identify Tu quoque fallacy:

Simpler version of the idea: "You can't accuse me of being corrupt when you have taken donations from special interest groups in the past," candidate B replies.

Simpler version of the idea: Furthermore, during your tenure as mayor, there were several instances of misconduct by your staff. (With Wordtune I realized that the argument started to break down here itself. Instead of addressing his own misconduct, candidate B had gone so far as to attack candidate A’s staff.)

Simpler version of the idea: It is difficult to talk about corruption when your own house is out of order.

When you put together the simpler sentences it’s clear in multiple places how poorly this argument is constructed.

Candidate B never defends his own stance. Instead he attacks candidate A’s:

- Own corrupt practices

- Staff

- Governmental operations

Now that we’ve dug deep into logical fallacies, let’s also take a look at how and when authors use them intentionally.

How to use logical fallacies intentionally

Oh yes we flipped the script.

Being able to spot logical fallacies is a super power. It makes you authoritative, credible, and trustworthy. And once you know how they work, you can use them to make your writing more interesting and structure complex arguments.

Here’s how I use them:

1. To create a sense of irony or sarcasm:

By highlighting the absurdity of certain arguments. For example, a character may use the ad hominem fallacy to attack another character, highlighting their own prejudices or insecurities. This can be used to create a sense of humor or to comment on the flawed reasoning of the character.

2. To create suspense or tension:

By obscuring the truth or creating confusion. For example, a character may use the slippery slope fallacy to argue that a seemingly small action will have disastrous consequences, heightening tension. (How often have we seen politicians do this?)

3. To create a sense of drama or conflict:

By pitting characters against each other. For example, a character may use the straw man fallacy to misrepresent the arguments of another, creating a sense of conflict between the characters.

In this example, Character 2 is using the straw man fallacy by misrepresenting Character 1's argument and implying that they have a hidden agenda, creating a sense of conflict and tension between the characters.

4. To create a sense of mystery or intrigue:

By obscuring the truth or creating confusion. For example, a character may use the no true scotsman fallacy by creating ambiguous definitions and let the reader’s imaginations take the lead.

Resources to improve your logical reasoning

1. Book: The Art of Thinking Clearly, Rolf Dobelli

A guidebook for your brain, this book teaches you how to avoid cognitive biases and fallacies that may cloud your judgment. The author presents 99 logical fallacies and cognitive biases and provides practical and easy-to-use tips to help us avoid these traps and make better decisions.

2. TV show: How to Get Away with Murder (or most legal dramas)

Other than the fact that this show is extremely entertaining, in every episode the characters pick apart complicated real life situations to identify logical fallacies to solve cases.

Most of these takeaways are true for almost all critically acclaimed legal dramas.

In fact, I’d say the credit for my strong critical reasoning process goes to legal dramas both in the form of books and movies.

3. Course: Graduate Management Aptitude Test

5 years ago I was preparing to do an MBA so I studied the Graduate Management Aptitude Test in excruciating detail. This is when I developed a strong hold on critical thinking. It has a dedicated section on Verbal Reasoning.

A note on dealing with logical fallacies

I’d like to reiterate: logical fallacies are a normal part of human life. They emerged and got strengthened because evolution rewarded quick decision making in fight or flight circumstances. When fighting predators, homo sapiens had to quickly decide what to do and logical fallacies reduced friction. That’s why they’re so hard to spot. They’re a part of our subconscious mind.

So cut yourself some slack as you evaluate and remove them from your writing. The best you can do is practice every day and utilize all possible resources to strengthen your logical reasoning abilities.

%20(1).webp)

.webp)